Garfielf King of the Sunday Funnies Recreators Alicetica

Peter Maresca's quest to preserve the look and feel of America's original Sunday comic strips by becoming an "accidental publisher"—and printing unusually large books

Peter Maresca calls himself "an accidental publisher." The accident began when in 2004, with the approaching centennial of Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland, he decided "the world needed to see these masterpieces in the original format before they went the way of all cheap newsprint." That meant making a book of incredible proportions (16 by 22 inches). He took his project to the usual art book publishers, and while all appreciated his zeal, they felt it was impossible to publish and distribute such a large book. "The only option was to publish it myself."

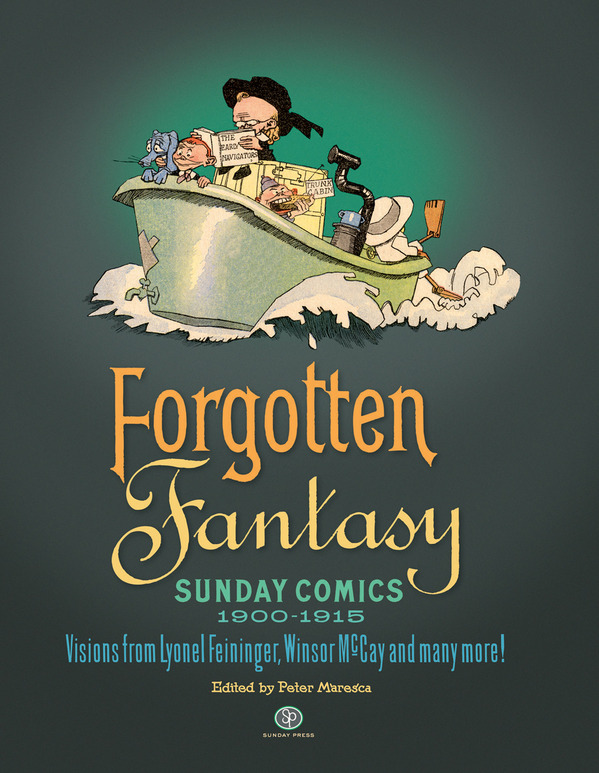

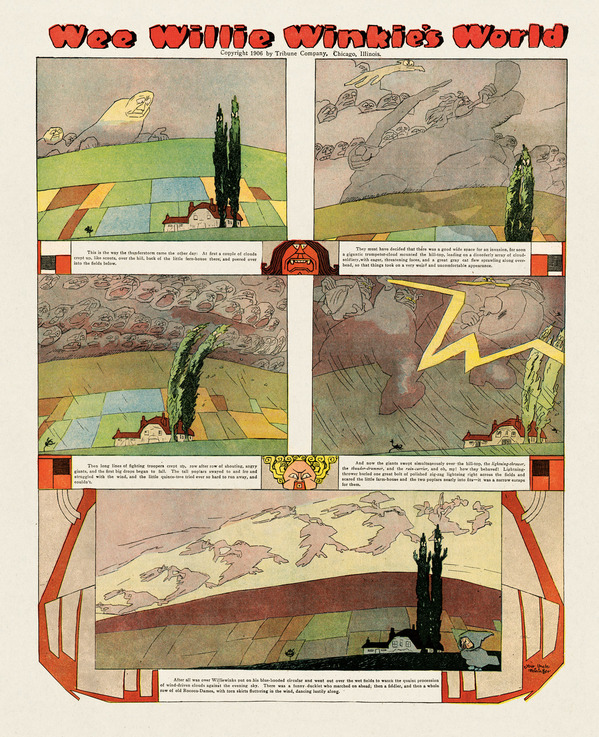

The Nemo book was the first of other equally large volumes documenting the Sunday Funnies, including the most recent Forgotten Fantasy: Sunday Comics 1900-1915, a gorgeous collection, including Lyonel Feininger, Winsor McCay, George McManus, Gustave Verbeek, and more, making Maresca and his Sunday Press the veritable reliquary for a slice of America's most fragile pop cultural artifacts.

After a few days spent luxuriating in this coffee table-sized extravaganza, I contacted Marersca for an interview about why and how this latest volume came about.

But first, what prompted you to accidentally make these enormous books?

There is probably a big "dorky collector" factor. I've been collecting comic strips since 1970. All collectors love to show off their treasures, and here was a way to share my collections and not have to worry about over-handling and damaging the material—or having masses traipsing through my house.

How difficult has it been to maintain the qualitative standard you've created in these volumes?

I'm not sure how to measure the difficulty, since I have never published in any other way, but production probably takes more hours per book than most in this genre. Restoration has to be incredibly detailed, since at full size you can see right down to the dots and screens of the original printing process. And a lot of time is spent traveling. I work closely with the designer, so in most cases this means meeting with Philippe Ghielmetti in Paris. I also feel the need to oversee the press checks in Asia, in order to be sure the colors are just what I'm looking for—imagining what the page might have looked like on the original newsprint while keeping just a hint of the aged yellow feel.

In the best of circumstances publishing is hard (like comedy compared to death), but at the scale you are doing it, how has your venture profited?

Anyone with business sense might have stopped after the second book. But there was much more I wanted to make available, so the success of the Little Nemo book and sales of foreign rights have subsidized the production of the other books that have not been as successful. I guess if I can make the books I feel are important and keep from losing money, I consider that profitable. Though I hate to think about what my hourly wage might be.

Let's talk about the latest, Forgotten Fantasy: Sunday Comics 1900-1915. This has so many lost and indeed forgotten works. What were your selection criteria?

The idea from this book came out of a discussion with Art Spiegelman after my second book, Sundays with Walt and Skeezix. I was seeking his advice on what to do next, as there is no way the market (or collectors' bookshelves, for that matter) could support full-size collections of every worthwhile comic strip, but I wanted to be sure all were represented in this format. So the plan was to create an anthology series of books: Giants of the American Comic Strip, covering all the great comic strips through the 1950s.

The first volume was to start with the earliest color Sunday comics in 1896, when the medium was inventing itself, to 1915, when syndicates and creative formulas were firmly in place. But I discovered there was too much wonderfully rich material in these early years and we needed to split it into two volumes. The obvious thematic subset was that of the Fantasy comics. So much of the beauty and originality of the early comics is found here. Plus, given the awareness of Little Nemo, starting with this fantasy volume would create an accessible bridge to the more esoteric material of the formative years of comics. But I did not realize until we had assembled the final contents just how essential this book would be in telling the story of America's first great form of popular culture.

Where did you obtain the original pages?

Each book starts from my own collection, which covered most of what was needed for the first books. For this latest volume, the comics were more varied and numerous than in any previous book. The collection of early Fantasy comics I had amassed over the years was filled with gaps, so to find complete the runs of several strips, and to get the best possible copies, my pages were supplemented by contributions from other collectors.

How long did it take to develop this from conception to finish?

It takes about six to nine months to get everything for one book assembled and ready for the printer. After the presses it takes about six weeks to bind the books (they need to be done mostly by hand) and another month for shipping. This one took longer than most because the material came from different collectors here and in Europe, and there was a larger amount of background material needed.

How are you distributing the book?

We do website sales and other direct distribution to our regular customers and retailers, but the bulk is through Diamond Comics, Last Gasp, and Ingram. We do our own storage and fulfillment, which, due to the size of these books, is the biggest single expense we have outside of the printing.

In addition to the artwork, you've peppered the book with history, brilliantly designed in a period newspaper style. What is your process of research and discovery?

As for the design, Philippe and I came up with that as a way not only to give the material a period feel, but also to enable us to offer articles of different length and content in a readable and familiar format. The exception was in Sundays with Walt and Skeezix where Chris Ware correctly gave the book a design that fit with the series of daily Gasoline Alley comics he was doing with Drawn and Quarterly publications. For the text material, we look to writers, historians, and creators with a unique knowledge and perspective on a particular artist, strip, or theme. Over the years I have developed a network of international comic lovers to contribute to this process, and hope to find many more.

What among these Sunday rarities is your most surprising or revealing?

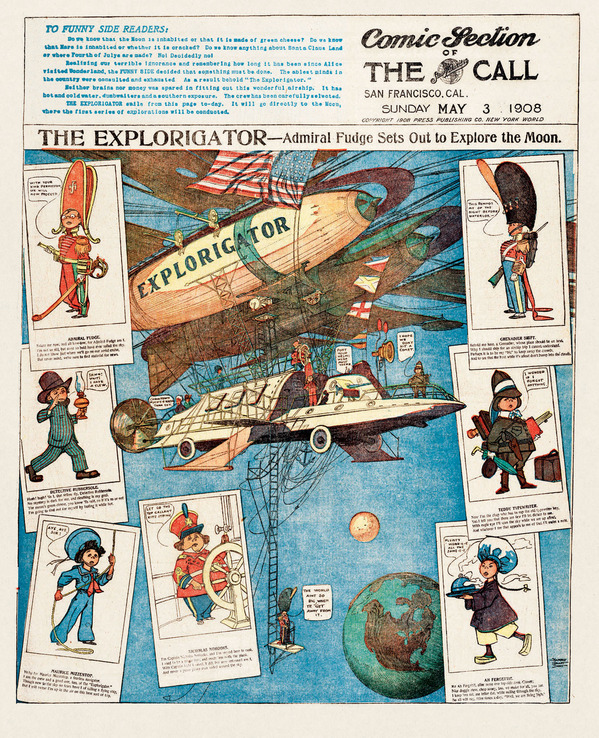

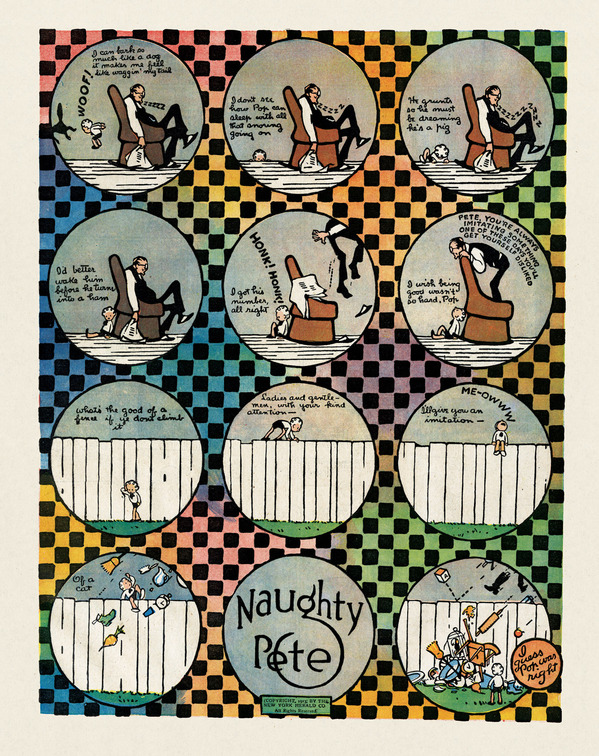

The genius in the work of Lyonel Feininger and Winsor McCay is well established. But two titles in the Forgotten Fantasy book really stand out for me, and I think will for most readers: The Explorigator and Naughty Pete. Both have had sample pages printed in smaller format, but to see the entire collections in their original size is indeed revelatory. The Explorigator (1908) by Harry Grant Dart was the first true science fiction series of the comics. Many pages display a "steampunk" sensibility 100 years before it became a popular comics sub-genre. Charles Forbell's Naughty Pete (1913) is unlike any comic strip of its day, with a look that is decades ahead of its time. In theme and design you can sense the work of Frank King, Charles Schulz, Jules Feiffer, Bill Watterson, and, of course, Chris Ware.

Bill Blackbeard, the father of comic strip documentation, recently passed away. Where does your venture compliment or diverge from his efforts?

Bill was a friend and a mentor. I don't think there would be a Sunday Press if it weren't for Bill Blackbeard; his early reprint collections inspired me to seek out the more obscure comics, and his strong support in getting my publishing venture started was invaluable. My upcoming multi-volume anthology series is an oversized version of Bill's own "Smithsonian" comics collection. As the Über Collector, Bill appreciated what I was trying to do with Sunday comics, something he was not able to do dealing with established publishers: to show classic strips in their original form, the way we first saw them, the way we fell in love with them.

What's next on your horizon?

I hope to continue with the Giants of the American Comic Strip anthology series starting with Founders of the Funnies (1895-1915) followed by collections of the humor strips of the teens and twenties, and then the adventure strips of the thirties. I've also got a special project in the works that combines the classics with more modern comics. After that, given my continuing decline in lifting ability, I think I'll try and make smaller books.

Images: Courtesy of Peter Maresca

spencersionceend1960.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2011/06/the-king-of-the-sunday-funnies/240188/

0 Response to "Garfielf King of the Sunday Funnies Recreators Alicetica"

Postar um comentário